In a recent post, I discussed how CBDCs can revolutionize financial aid. For the past few years my team and I have focused part of our efforts on blockchain education, including high level seminars to multiple government departments in Israel and abroad. We also held discussions with the Bank of Israel as they explored their interest in a CBDC. Ran Melamed, head of Research at the Hexa Foundation, detailed our thoughts on CBDC to the BOI here. In this post, as well as in a few of the ones that will follow, we will break down his paper on CBDCs, particularly what they are, their advantages and challenges and other related topics.

Central Bank Digital Currencies (CBDCs) are one of the hottest monetary topics, involving macroeconomics, blockchain technology and even philosophical and sociological discussions concerning the essence of money. As such, they have been the subject of multiple research papers published by dozens of central banks and financial institutions over the last few years. On a fundamental level, some have broached discussion on the relevance of centralized fiat currencies in the modern world and what place they might have -- if any -- in the future.

Central banks are known for being conservative, and rightfully so. They carry the heavy burden of implementing a state's monetary policy. Their key asset, aside from economic competence, is their reputation. The base of any solid economy is a strong, professional and reliable central bank, that is trusted, both locally and globally, to think things through rather than making hasty moves. This requires extreme caution given the potential consequences of a given monetary policy. Attention must be paid to the timing and type of policy, and of course the benefits and drawbacks must be weighed and due diligence conducted during the entire implementation process. It is understandable then that Central Banks would be hesitant to adopt innovative advances.

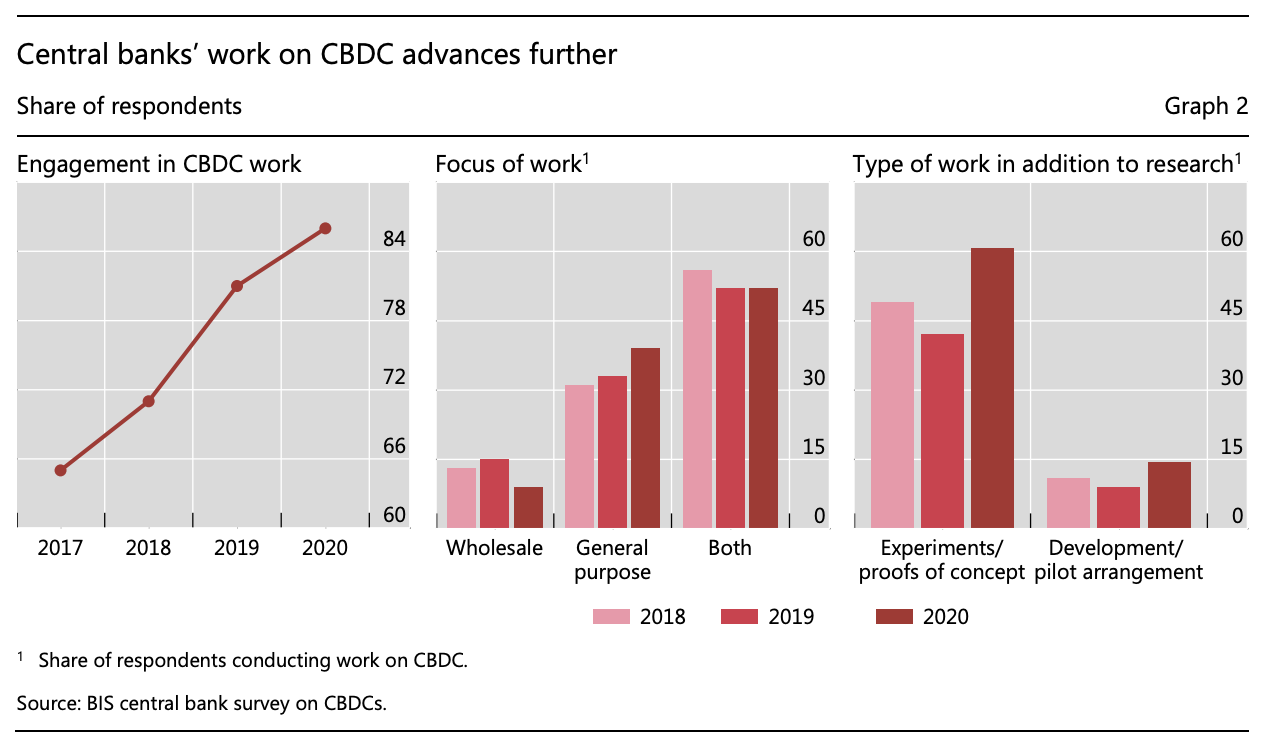

During the past months CBDCs have gained significant momentum, with growing interest from the world's leading central banks. According to a recent BIS survey, 86% of central banks are engaging CBDC, most of them (60%) have already launched a POC or some sort of another experiment, while 14% are moving towards development and pilots. Just to name a few of the leading economies in which the topic is under intense discussions are: USA, UK, China and Israel.

CBDC is a form of money, however there is no consensus on its definition. When reading the most cited definitions carefully, one can gather some general principles and an emerging standard. In order to find a common denominator that can serve as a foundation for discussion, we rely on two commonly accepted definitions: that of Bech and Garrat and that of Berentsen and Schär:

Bech and Garrat's "Money Flower" defines CBDCs as a form of money that is:

Widely accessible -- Central banks already offer settlement accounts (or balances), but they are only accessible to commercial banks. However, CBDCs would be available to the general public,

Issued by a central bank -- As opposed to bank deposits, other digital payment services or virtual currencies,

Peer-to-peer -- as opposed to bank deposits

Digital -- As opposed to physical cash, which satisfies only the three other aforementioned traits of this definition

Berentsen and Schär look at it differently, by examining three criteria: monopoly vs. competition, virtual vs. physical, and centralized vs. distributed. Accordingly, they see two types of CBDCs that are relevant for our discussion:

Issued by a central bank -- just as Bech and Garrat advocate,

Virtual -- similar to, if not interchangeable with, Bech and Garrat's "digital" requirement, and

Centralized or distributed -- Herein lies the main divergence between the two views (and potentially two types of CBDC). If a CBDC is centralized, Bech and Garrat refer to it as "Central Bank Electronic Money." If it is distributed, the pair call it a "Central Bank Cryptocurrency."

Assuming the approaches above can be reconciled and a clear working definition of CBDCs agreed upon, there are certain design features that would still be a matter for debate. Features of one CBDC in turn might contrast with CBDCs issued by other central banks. These features are analyzed by BIS Committee on Payments and Market Infrastructures:

Availability -- The bank may determine any sort of limitations on using the currency, e.g. time, location, duration, sector, etc.

Anonymity -- User anonymity may vary, i.e. total anonymity to maximal identification required

Transfer mechanism -- In our view, this is the most strategic decision the central bank needs to make, as it stands at the heart of the discussion whether a CBDC ought to be centralized or distributed. We explore this topic later in this paper

Interest bearing -- As with any form of a central bank's liability, it may bear positive, negative, or zero interest, accordingly resulting in different consequences

Limits or caps -- Such limits may be necessary to prevent and mitigate any potential misuse of the currency, whether intentional or not

The features above demonstrate the potential variations that CBDCs might have and how they satisfy each respective central bank's laws, regulations, policies, and targets.

It seems that the main reason for the increasing interest in CBDCs is that they encapsulate the convergence of recent financial and technological developments. For many, the biggest technological breakthrough with blockchain technology was inventing a mechanism for exchanging value by creating digital scarcity. The revolutionary change here for finance came in the notion that a digital currency had been created privately with decentralized software, and without the intervention or permission of a central bank. With that, one of the base assumptions of monetary theory, i.e. central banks control money supply, had been shattered.

Another key trend is the growing volumes of digital payment transactions worldwide. Digital payments through e-wallets have been growing significantly in the last few years and growth is expected to accelerate significantly in the future. According to Capgemini & BNP Paribas' World Payment Report 2020, the volume of non-cash transactions grew by 14% in 2018-2019, the highest surge in the past decade, reaching 708 billion transactions worldwide. While COVID-19 tamped down future estimations, the trend is clear and by 2023 the report predicts growth of more than 50% to 1.1 trillion transactions. This growth is mostly driven by smartphone penetration rates, the falling cost of data, and improved security. Banks still play only a minor part in this market despite their inherent strengths, e.g. client trust, network, regulatory expertise, etc. However, we estimate that this will change and that banks will gain a substantial market share, especially as these markets become more regulated. It is our opinion that banks should and will eventually provide their own e-wallets as part of a larger solution that will include additional instruments and services.

While these trends have not been overlooked by central banks and financial policy makers, they are still having difficulties providing a timely response in the form of new regulation. We believe that CBDCs can assist in this process, mainly as it provides the public with a government-certified e-wallet.

Our goal in this post was to set the grounds for better understanding what a CBDC is. In our next posts we would like to dig deeper and analyze their advantages and disadvantages.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.