This is Part II of a series on Proof-of-Stake’s growing influence in crypto and blockchain, as well as issues its implementation still faces. This is an expanded version of a talk I gave for Blockchain Academy on June 11, 2018.

Check out the previous post for a high level introduction to PoS as a paradigm shift from PoW.

In this post we will investigate the PPCoin system as a PoS case study. From this early attempt at PoS we will understand some of the general challenges the PoS paradigm must resolve in order to yield resilient and secure blockchain systems.

PPCoin was launched on 19.8.2012 as the first blockchain to actually incorporate Proof-of-Stake, or PoS. It is not a pure PoS blockchain, but a hybrid one with interchangeable use of Proof-of-Work (PoW) and PoS to form blocks (checkout this block explorer). Put another way, a PoS block can be proposed on top of a PoW block or vice versa.

The main motivation behind PPCoin’s creation was Bitcoin’s diminishing returns: As the reward for mining a PoW block reduces, so will the incentive to mine them (unless fees are dramatically increased, which people would like to avoid). Since PoS blocks are much cheaper to produce and should serve as a long term solution, the rewards they entitle are much smaller but remain constant, aiming at a conservative 1% yearly inflation rate.

This is a departure from the way PoW models mint new coins. The core idea of PPCoin was to include proofs of coin age consumption in blocks (rather than proofs of having done intensive computational work). A 10-unit coin (i.e., UtxO with value 10) that was created 90 days ago is said to have 900 coin days of coin age.

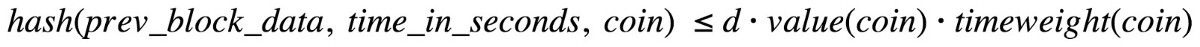

First, we note that PoW blocks are found similarly to Bitcoin’s blocks. PoS blocks are different. Each PoS block must spend an old coin, thus consuming its coin age. An old coin is eligible to create a PoS block at time time_in_seconds if:

Where,

If the formula is satisfied, the owner of coin can build a block, include in it a coinstake transaction that spends coin for a new transaction output, whose value is slightly larger than value(coin) (by 1/100 for each year of coin age consumed, equivalent to a 1% yearly inflation rate).

The main difference between a PoS block and a PoW block is the nonce field. In a PoS block, each coin in the blockchain has one attempt per second to be elected (i.e., satisfy the formula). If the attempt succeeds, the stakeholder in control of the coin can publish a block. Otherwise, she would have to wait one second and only then try again. This is a good place to emphasize two differences relative to Proof-of-Work mining:

This all seems very promising until now. Let’s examine the system more deeply by looking at prev_blocks_data. Here are three possible alternatives:

The analysis above should have convinced you that having a fair stakeholder election process isn’t easy to design. However, this is not the only problem with PPCoin. Another interesting problem is that of rational forks.

To understand this problem, let’s rethink PoW for a second — a miner in a PoW-based chain that knows a single tip constructs a block on top of it and checks its validity. She immediately gets a response. If the block is valid, she publishes it. Otherwise, she increments the nonce and tries again. The point is that at any point in time her compute resources are fully utilized. Thus, if our miner was introduced with an alternative tip she would have to decide how to split her resources. Her best strategy is to devote her resources where it’s most likely that the network would include her block, if indeed she were lucky to find one, as a part of the canonical chain.

Now, let’s consider what happens in PPCoin. Similarly to PoW, a stakeholder tries to extend the tip she knows and immediately gets a response. If her block is valid, she publishes it. Otherwise, she must wait one whole second before her next attempt. During this second her compute resources are unused. Thus, as she waits, she has nothing to lose (and little to gain) by pointing her resources where potential blocks are less likely to become part of the canonical chain. Specifically, if a stakeholder is presented with two competing tips (at the same height), she is unlikely to tie her hands behind her back and try to extend only one of them. She is more likely to opt to gain more (expected) rewards by keeping both forked chains.

If such a strategy is enforced by all stakeholders the chain would suffer frequent reorgs and the system would be much less stable. This problem deteriorates as the block interval decreases and thus a PoS system in the spirit of PPCoin wouldn’t enable scaling or lower confirmation times.

Another way to think of the above problem is what’s known as nothing-at-stake. Stakeholders may attempt attacking the main chain by building alternative (secret) chains. They would try to extend recent blocks all the time until at some point they find a sequence of blocks. Since these attempts are practically free, they have nothing to lose. If they see the main chain becomes much longer than their hidden fork they would simply abandon it and try again from scratch with a more recent block. It is important to mention that while the attack takes place they could try to extend the main chain as well to make sure they don’t suffer any reward losses. Conducting such an attack would eventually succeed, but worse, it would bare no cost to the attacker.

The main reason for the nothing-at-stake problem in PoS systems is the fact that blocks are “cheap” to produce and don’t require “work”. In PPCoin, this problem is directly related to the way leaders are elected to produce blocks. We’ll try to separate the two problems in the next posts and discuss ways to mitigate each one. But first, how did the PPCoin developers mitigate these problems in their system.

The analysis above relies on this paper (section 2) by Iddo Bentov et al.

To make sure stakeholders don’t manipulate the election process of future coins for PoS blocks, a rather complicated function was chosen for prev_blocks_data (look here for more details). PPCoin developers designed prev_blocks_data to reduce the influence a stakeholder has by choosing her block this way or the other. However, it is difficult to assess to what extent this is actually achieved. In the next post, we will discuss “low-influence functions” which are another option to achieve this.

Additionally, the PPCoin developers addressed the problem of rational forks (and hidden chain attacks) via a checkpoint mechanism. Checkpoints disincentivize any attempts to build hidden chains — any long reorg would simply be ignored by the checkpoint mechanism that de facto determines the “true” chain.

Of course, the problem with developers checkpoints is that they serve as a point of centralization that the system is dependent on for stability. In addition, it seems the leader election process is vulnerable to manipulation by the stakeholders.

As we’ll see in the next few posts, these were indeed the problems PoS system designers came to solve: 1) generating unpredictable and non manipulable randomness for leader election and 2) coping with the cheap production of blocks (both for short-range attacks like chain convergence or hidden chain attacks, and for long-range attacks like syncing new nodes).

Another issue we need to relate to is that in PoS systems, at least the one offered by PPCoin, stakeholders gain very little rewards and are thus less motivated to actively engage with the block production process. Participation level might then become a problem as many stakeholders may stay offline for long periods of times.

At this point, I’d like to mention that there were three major evolution steps in PoS design. First attempts tried to mimic Bitcoin’s PoW quite naively and were prone to many vulnerabilities. These attempts include PPCoin (and its descendants Nxt and BlackCoin) and Iddo Bentov’s Proof-of-Activity and Chains-of-Activity.

Later attempts incorporated a Byzantine fault tolerance layer (BFT) over the native chain selection rule. In a sense, the longest chain selection rule was replaced for more secure alternatives based on a thirty-year-old body of research into BFT consensus algorithms such as PBFT. BFT algorithms typically satisfy mathematical properties, but rely on specific assumptions that don’t have to be met in a real-world implementation. Particularly, BFT chain selection rules can reduce the need for synchronous communication to guarantee consistency (which enables a significant speedup in the block rate), but assume that only a super-minority of the participants don’t follow the protocol honestly.

We will discuss this point in detail in the following posts, but I’ll say now that incentivizing correct participation has great importance in PoS design. First attempts at repurposing BFT algorithms for PoS were made by Tendermint and Algorand.

Both in traditional BFT algorithms and in modern PoS suggestions, the role of proposing blocks and validating them is played by the same entities. A third generation of PoS systems, led by Casper FFG, separates block production from block validation. One service continuously spits blocks, forming a tree-like data structure through hash chaining. A separate validation service determines an ever-growing finalized branch within the tree through a BFT protocol driven by PoS.

This approach reduces some of the difficulties in implementing PoS-based blockchains by relying on a PoW-based block production service. It enables a gradual migration to PoS by incorporating the PoS service atop a functioning PoW chain. This is exactly what Ethereum is planning with Casper FFG, with the intention of replacing the PoW block production service for one that relies on PoS at a later time.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.