The past few weeks have been highly turbulent for Bitcoin and cryptocurrency. After Elon Musk’s honeymoon period of showering love over the cryptocurrency, Tesla made a surprising announcement that it will stop accepting Bitcoin as a means of payment for cars out of environmental concerns. A few days later, China announced that it will ban financial institutions from offering Bitcoin services, which was apparently only the first measure, as it was followed by its crackdown on Bitcoin miners, aiming to eliminate this activity in China.

Headlines on Bitcoin’s energy consumption are ubiquitous. People often equate energy consumption with pollution, and thus the current attitude towards Bitcoin is that it is “harmful” to the planet. The industry is placed under this type of scrutiny because unlike other industries, Bitcoin energy use is much easier to calculate. We can not as easily measure the global footprint of other industries. How much energy does it take to produce and ship disposable face masks around the world and assist in the prevention of a pandemic spread? If the carbon emissions from producing and shipping face masks were extreme would there be an uproar of demand to cease these activities? I would like to hear Senator Warren’s opinion on that but my guess is most likely not. Everyone knows there is a huge positive social impact from facemasks. I would argue that there is a huge social impact from Bitcoin as well. Anyone living in Venezuela can attest to the financial lifeline the people of Venezuela have received from cryptocurrency. We should stop and think about this before condemning Bitcoin as bad for the world. We should look at El Salvador, which recently approved the currency as legal tender, and understand that there is a true humanitarian reason for that approval.

To put our discussion in context let me first briefly explain what miners are and what their importance is in the Bitcoin ecosystem. In a centralized platform, there is a single entity that makes all the decisions, most importantly the validity of transactions. One of its key challenges is securing the network so that no unauthorized entities can penetrate and interfere. A decentralized protocol involves multiple entities (nodes), none of them is in charge. Consequently, security becomes less of an issue as there is no single point of failure and hacking the platform requires attacking multiple nodes at a significantly shorter time interval. However, the challenge does not dissipate, it only transforms. The nodes must reach a decision together, so now the challenge is governance and collaboration. This is called consensus.

There are two main methods for reaching consensus in a blockchain protocol: proof of work (POW) and proof of stake (POS). The latter is straightforward – a block is approved by the majority of votes. Each node’s vote is proportional to the amount of tokens it had staked, i.e. blockchain’s version of skin in the game. On the other hand, POW is trickier, therefore I will not delve into its bits and bytes. The simplest explanation is to think of a complicated mathematical puzzle that requires substantial effort, for instance solving a set of equations. Solving them proves you met the challenge, i.e. did the work, therefore the protocol compensates you with a fee. Each new step introduces a more difficult challenge than its predecessor while interlacing it to the new problem, thus reinforcing the entire puzzle’s consistency. The process of solving this mathematical challenge in return for the reward that follows is called mining. The combined computation power required to mine new Bitcoin and process all transactions is called hashrate. By the way, both Bitcoin and Ethereum are POW, with the key difference that Ethereum’s next version (Ethereum v2.0) which will be rolled out in several phases over the next few years, will be POS.

As the value of Bitcoin appreciated the incentive to mine it has grown respectively. As a result, we have witnessed the crypto-technological equivalent of an arms race, in which miners have constantly upgraded their equipment, seeking to optimize their solutions, i.e. solve the challenge faster and get a higher reward. While in the first years of Bitcoin you could mine Bitcoin using a standard PC setup, miners soon realized that a tweaked computer, still with standard hardware, does a much better job. Finally, it was evident that the solution is dedicated equipment, designed, manufactured and operated with a single goal in mind – mine Bitcoin as efficiently as possible. The economic model is straightforward, optimizing the investment in equipment and minimizing variable expenses (mostly electricity and cooling) to maximize ROI (measured in Bitcoin mining rewards). Whoever has the upper hand knows that the advantage is only temporary, and that everybody must run faster just to stay in the same place. Therefore in many aspects the name of the game has become the ability to minimize energy costs in any way possible.

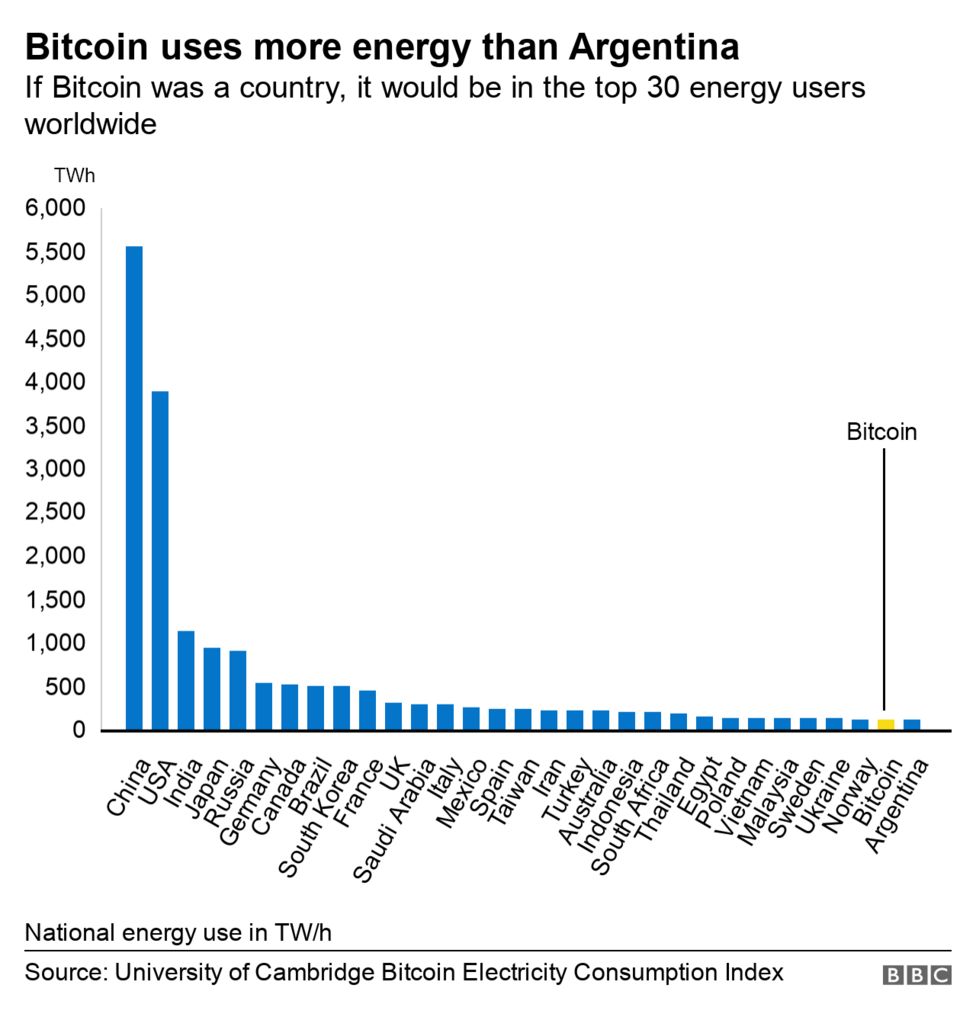

Because of POW, blockchain mining requires substantial amounts of energy. As the hashrate grows, so does the energy consumption, and the debate about it. It was often argued that the Bitcoin industry’s energy consumption was higher than Argentina’s consumption. While this may be true, the more important question is what are the environmental consequences of this consumption, and to be even more accurate – what is Bitcoin’s carbon footprint?

A recent HBR piece finds that the lowest estimates suggest that 39% of Bitcoin energy consumption is carbon neutral, which is more than double compared to the US grid. This is attributed to some simple reasons. The first is that Bitcoin can be mined anywhere and is not limited whatsoever by the distance to its end users. In addition, power storage and energy transport technologies pose a severe limit on the distance between a power plant and consumers. As a result, it often occurs in certain areas that renewable energy goes to waste because the supply outpaces demand, for instance in Iceland, or certain provinces in China. It is not surprising that these places attract miners who seek to minimize power expenses. For instance, during the wet season in China, much of the mining is done in provinces that rely heavily on hydroelectric power, using clean energy that would have otherwise gone to waste.

The same piece estimates not only that most of Bitcoin’s energy consumption originates in mining rather than in using it, therefore as mining expansion is expected to reduce so will its energy consumption.

Given all the above, we can now try to analyze the effects that the Chinese authorities’ measures had on the crypto markets, given that it is estimated to account for more than 60% of Bitcoin’s hashrate. The most crucial measure was banning institutions from Bitcoin mining and trading at the end of May, which triggered an immediate drop of 15% in Bitcoin and Ethereum’s price. Aside from the immediate effect on the overall market sentiment, it is presumed to have created a strong sell pressure on miners who needed to cash out their positions ASAP, either to finance new mining activities outside China or completely restructure their business.

It is difficult to explain what are China’s motives behind these measures: did it have to do with its strategic plan for a digital Yuan, did it have to do with genuine environmental concerns and its climate plans, is it related to other measures taken against certain allegedly perceived financial threats on China (e.g. Ant Group) or was it something completely different? We may never know.

Whatever these reasons are, it will be interesting to follow on future effects that are yet to come, as Bitcoin mining efforts are about to be redistributed geographically. Reducing the concentration of Bitcoin mining in China is overall seen as positive for the cryptocurrency, if only for the obvious reason of not having so much of it mined within the borders of an authoritarian regime. It has also resurfaced the important discussion of Bitcoin’s energy consumption and its environmental sustainability in a constructive approach, unlike in certain previous occasions. There was even the announcement of formation of the Bitcoin Mining Council, that despite the justified criticism it spurred could be in some awkward way a move in the right direction.

Perhaps Elon Musk should have been more patient with Bitcoin. Forced now to find alternate sites for mining centers, the industry may develop in a smarter and cleaner way, eventually making the carbon footprint of Bitcoin no larger than Elon’s electric car empire. Given the added value of providing financial security for the unbanked, globally, this blog writer has high hopes for the cryptocurrency’s future – and sees clear skies beyond the smog.

Netta Korin is a cofounder of Orbs. Prior to Orbs Netta worked for many years on Wall Street as a hedge fund manager. She later held senior positions in the Israeli government, including Senior Advisor in the Israeli Ministry of Defense to General Yoav (Poly) Mordechai, Head of CoGAT, and Senior Advisor to Deputy Minister Dr. Michael Oren in the Prime Minister’s Office in Israel, focusing on Palestinian issues. Netta has held board positions in several non-profit foundations in both Israel and the United States. She also founded The Hexa Foundation with the aim of promoting blockchain for social impact and harnessing the mind power of the Orbs ecosystem and network to help solve the region’s and the world’s most pressing humanitarian problems.

For more information please contact Netta Korin (netta@orbs.com)

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.