About two months ago Marathon (NASDAQ: MARA) announced that it had mined the first-ever Bitcoin block that is fully compliant with US regulations. The company applied exclusively licensed technology that allows it to refrain from processing transactions from people who are listed on certain databases (e.g. OFAC, SDN, etc.). While Marathon is not considered a particularly influential miner in terms of its hashing power of the total hashrate, this move positions the company as an innovator in its approach towards future potential integration of Bitcoin with global AML regulations. This announcement, as well as recent posts of mine discussing Bitcoin mixers and other Bitcoin-related events in China, made me ponder a bit about “clean” vs. “dirty” Bitcoins.

One may argue that this is total nonsense, as Bitcoin is fungible (the more sophisticated term for fully interchangeable). Therefore, all Bitcoins are alike and cannot be differentiated one from another. Technically, this is true on a surface level. However, as it turns out, like in many other concepts involved with blockchain, it is more complicated than that. As I will explain, it is not only that certain Bitcoins are in effect worth more than others, but also that the differences may stem from the moment they were mined. Some Bitcoins are considered “dirty”, such that most exchanges, brokers or anyone who knows anything will never accept them. Others are considered “super-clean”, sometimes referred to as “virgin”, to the extent that some people would even be willing to buy them at a premium. Naturally, most Bitcoins are neither, they are standard and fungible, as you would have probably expected. Still, let us delve into the other two “types”, which are more interesting,

One of the things that strikes me is that many people still believe that Bitcoin, as well as many other cryptocurrencies, guarantees complete user privacy and anonymity. While digital wallets may be anonymous to some extent, Bitcoin transactions are immutably documented on a public ledger, and the technology that tracks and analyzes them only improves with time. As a result, any crime committed using Bitcoin will leave an immutable trail of evidence, waiting for law enforcement agencies to put enough time and effort in order to investigate and solve it. This inherent and ultimate traceability is the reason that Bitcoins may be tagged and differentiated.

The main and obvious reason that certain Bitcoins are considered as “dirty” is due to suspicion of being involved in illegal activity or “mixing”. In a nutshell, mixing is an attempt to hide the source of a transaction. However, when there is smoke there is fire, which raises the question of why one would mix a transaction if she has nothing to hide. Thus, as mixing has become a standard feature in many digital wallets, the technology that detects mixing has also made substantial progress. Even though these techniques are mostly probabilistic and not definite, they provide a decent metric to rely on. As a result, anyone who is aware of AML regulations, or just likes to play it safe, can block deposits that are suspected of originating in a mixed transaction. Due to a lack of regulation, there are no clear guidelines for anything regarding cryptocurrencies. Therefore it is up to service providers such as exchanges, brokers, OTC desks and others, to self-regulate themselves and establish policies for accepting and blocking incoming transactions. It is widely agreed that once tokens are sent from an account at a reputable service provider they are considered to be acceptable anywhere, making these service providers liable and cautious with regard to the incoming flow of tokens.

There is also the case of Bitcoin used as a means of payment in illegal activity, i.e. sent from blacklisted wallet addresses. Yes, Bitcoin is used by some to finance illegal activities (by the way, so are cash, (stolen) credit cards and bank accounts). Still, in situations when certain addresses are publicly known to be directly linked to criminal activities they are blacklisted in order to de-facto devoid the balances they hold. In that regard, it is worthwhile to pause and discuss what blocking a Bitcoin address involves. Unlike wire transfers, one cannot block an incoming Bitcoin transaction sent to her wallet. Therefore, in order to “block” a transaction, one has to send the incoming amount back to the source address, the sooner the better. A shorter response with no other transactions in the meantime would make it safer to later argue that a transaction was indeed blocked, under the known Bitcoin protocol limitations.

The Silk Road is the most famous darknet black market that was taken down by US law enforcement agencies and one of the most fascinating crime schemes in the Internet era. Yet, I am more interested in one of the events that followed. About a year after it was taken down, the [US Marshals ran an auction to sell about](https://www.nbcnews.com/tech/tech-news/feds-auction-30-000-bitcoins-seized-silk-road-raid-n143091 BTC 30,000) that were seized, (circa 20% of the overall amount). This serves as a great example of how law enforcement can clean “dirty” money and redirect it back to the market, in a perfectly legal procedure. It was not the last auction of this kind, as the rest of seized Silk Road Bitcoins were later sold in a similar manner, as were confiscated coins in multiple other events.

This transition allows us to examine the opposite end of the spectrum, the “cleaner” Bitcoins. As a general rule of thumb, it is much easier to get Bitcoins dirty than to clean them, since the auctions mentioned above are irregular events that do not happen that often. Therefore, the best way to ensure that your Bitcoins are clean as a whistle is to try to catch them while they are young, i.e. as soon as they’re minted.

The Bitcoin protocol rewards participants for their efforts – mining new coins and verifying transactions. For example, in this transaction BTC 6.48 (consisting of a BTC 6.25 reward and fee BTC 0.23) were sent to the miner, noting explicitly that the coins are newly generated. Such transactions occur every 10 minutes (on average), when a new Bitcoin block is created. Unlike other transactions, there is no shred of doubt concerning the source of these Bitcoins and no one could argue they were involved in a financial crime. Consequently, some people would be willing to buy them at a premium, which, by the way, is considered suspicious activity. It is important to keep in mind that this cleanliness might vanish once they are sent to a new address, and is completely dependent on their new owner.

Knowing the miner’s identity makes things more interesting and might paint the minted Bitcoins from the beginning. For example, is the miner known to be involved with criminal activity (not having to do directly to mining), known for using certain kinds of energy (e.g. only renewable) and so and so forth? Any additional piece of information about the miner sheds more light and might tag the coin one way or the other. In that regard, one can only wonder how much the first BTC 50 ever minted by Satoshi Nakomoto(?) in Bitcoin’s first transaction ever, would be worth, if they were ever to be sent out of this address. While some may be willing to pay a fortune for them, others say they would be worthless, due to the panic this move might trigger in the Bitcoin community.

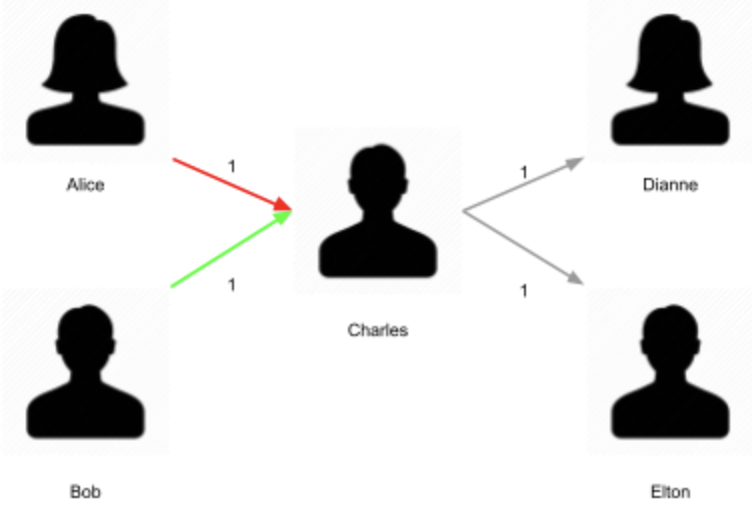

Before I conclude, let us discuss the following example that demonstrates the fragility of the Bitcoin system when it comes to clean and dirty transactions. Let’s consider 5 wallet owners: Alice, Bob, Charles, Dianne, and Elton. At first, Alice and Bob each have BTC 1, while the others have none. Alice and Bob each send their BTC 1 to Charles, who later sends BTC 1 each to Dianne and Elton. Now let us assume that while Bob is an honest person, Alice is a world-renowned criminal whose entire Bitcoin balance was gained in financial crimes. Once Charles accepted transactions from both into the same wallet address, he did one of two things – either he tarnished his wallet for good or he involuntarily cleaned Alice’s BTC 1. While Bitcoins have IDs, they are only preserved until they are spent (unlike US Dollars bills), therefore once they are accepted into a wallet they are “blended” with all the others that are already there. Neither Dianne nor Elton received a dirty or a clean Bitcoin, but a “plain” one. Neither of them is a HODLer, so when they send it to someone else, she will then have to decide whether to accept or block it, given her ability to analyze the transaction history on the ledger. And so it goes that as more transactions are approved the chances are higher for the next to be.

I would like to emphasize that the concepts discussed above, and particularly my definitions of “dirty” vs. “clean”, are far from being formal or standardized in any way. As of writing this, Bitcoin is still not regulated in many countries and was only recently accepted as a legal tender in El Salvador. Therefore, it is the responsibility of anyone who receives Bitcoin to make sure she knows who the sender is, in order to avoid potential trouble. I can only hope that regulation will be set sooner than later. Until then, my best advice would be a paraphrase of the famous Latin proverb, let the Bitcoin recipient beware.

We use cookies to ensure that we give you the best experience on our website. By continuing to use our site, you accept our cookie policy.